Svetlana Mintcheva // The Economics of Artistic Freedom

In January 2019 I interviewed Svetlana Mintcheva, Director of Programs at the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) and the founder of NCAC’s Arts Advocacy Project. Mintcheva co-edited Censoring Culture: Contemporary Threats to Free Expression (2006, The New Press) and has written and spoken widely on issues of artistic freedom. She has taught literature and critical theory at the University of Sofia, Bulgaria, and at Duke University, from which she received her Ph.D. in critical theory in 1999. She has also taught part-time at New York University. Our conversation focuses on economic influences on artistic freedom.

Karen Finley, “Yams up my Granny’s Ass” at Theatre Gallery, 1986

photo via Dallas Observer

C: In the 1966 introduction to Best Short Stories by Black Authors*, Langston Hughes writes, “some people ask ‘Why aren’t there more Negro writers?’ [. . .] Or how come So-and-So takes so long to complete his second novel? I can tell you why. So-and-So hasn’t got the money.” In the United States, funding for the arts limits who can make work and the artistic freedom they experience. Can you compare it to the influence of direct censorship?

S: I have a quote to answer your quote with. It’s about money and freedom and it’s by Anatole France, a French writer. It reads, “the law in its majestic equality forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges to beg in the streets and to steal their bread.” Money affects the choices we can make, and money in our societies is unequally distributed. No matter how impartial the laws may be, they have a different impact depending on where you stand in terms of the independence money affords. It’s the same for speech and art. When we look at arts funding through time, art is always dependent; on patrons, on markets, etc. Artists also need to pay bills, so they’re not above any kind of system of money and exchange and ownership that limits the freedom of what you can do in our societies. If you don’t have the time to create artwork, you can’t create it. If you have a full time job, you won’t have time to create artwork. Artists don’t have a position of exceptionality within a society which runs on money.

When public funding was a major issue in the U.S., that was not quite the question. In the ‘90s, during the Culture Wars over public funding for the arts, the question was: when someone funds the arts, can they determine content? How much can the person paying the artist determine what the artist is saying when that “person” is the government? The U.S. government hasn’t been traditionally very generous to the arts but in 1980, the National Endowment for the Arts had a budget which was at a historical high. Then the Culture Wars broke in Congress, with some conservative Congressmen lambasting the NEA for giving money to projects that some taxpayers found to be offensive to their values. Social conservatives were joined by fiscal conservatives, who always thought government should not give money to the arts at all. Yet both the American public and Congress believe the arts are good for society and business, as well as for the cultural image of the country, so they deserve support.

“Money affects the choices we can make, and money in our societies is unequally distributed.”

When we talk about arts funding, we aren’t talking only about supporting the individual because they need to express themselves, we’re talking about something that benefits everyone, the richness of the cultural environment, providing people with a kind of spiritual nourishment.

The question in the 1990s was: given that government agrees that the arts should be supported, should it have the right to exclude expression that may offend someone from its largesse? The First Amendment answer to this question is no: once the government decides to fund the arts it should not then discriminate against certain viewpoints. So, public funding for the arts survived the Culture Wars with some bruises (laughs), including grants to individual artists which were abolished on the federal level. However, the tendency in general is for public funding to shrink and the burden on supporting the arts to be now on foundations and individual donors.

C: When public funding shrinks, how does that tip the balance?

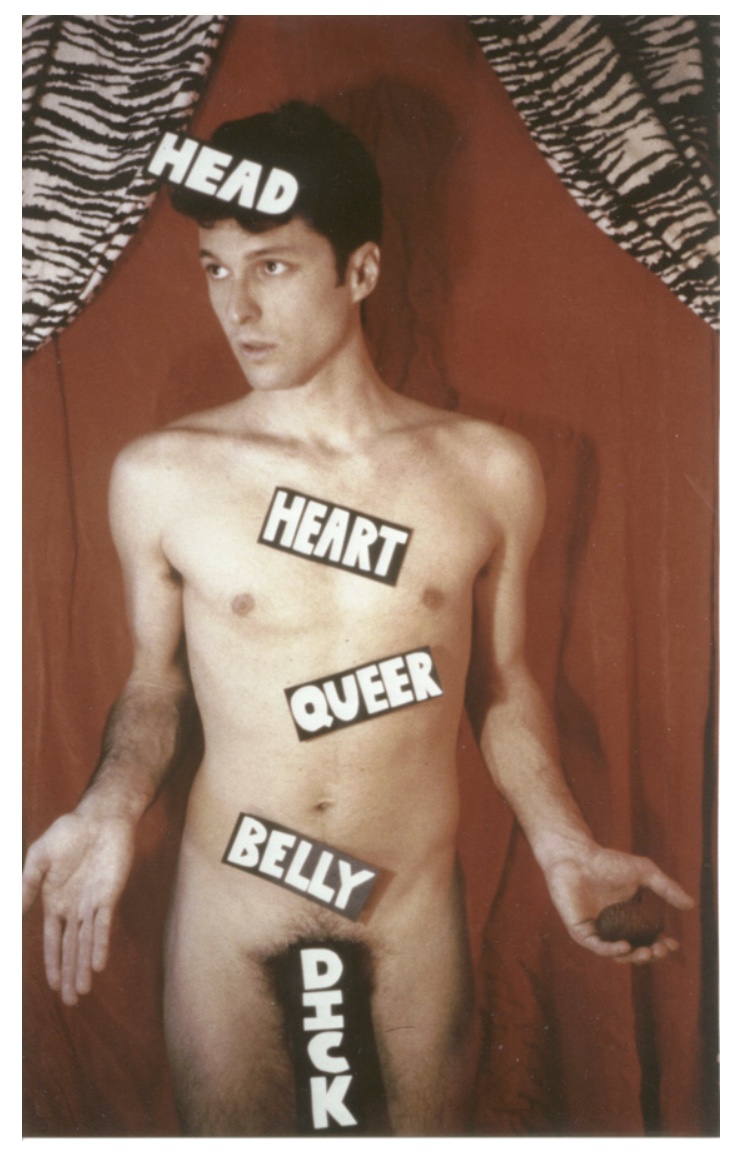

Tim Miller, still from My Queer Body 1992

photo via Hemispheric Institute

S: There is more private than public funding. When you look at influence, the key point there is private funders can fund whatever they want. They are not affected by the First Amendment and can freely decide to only support viewpoints they like.

C: Funding has such a sizable impact on whether or not a creative work comes into existence, as well as the circulation of that work. Paradoxically, funding can be one of the most invisible and unspoken parts of the art world. How does the filtering of NEA grants through museums and non-profit arts organizations affect the creation and circulation of new work, as opposed to awarding direct grants to individual [visual] artists? [The NEA continues to grant writers and musicians individual awards.]

S: The NEA is just one government agency funding the arts. State funding for the arts has always been much larger than the federal funding for the arts provided by the NEA. NEA individual artist grants were impactful not just for the financial support they offered, but even more as a stamp of approval. The process of giving NEA grants was important - a respected peer group of artists, professionals in the field, deciding - so the grants carried a lot of credibility. It was a seal of approval that made it “safer” for other funders, whether individual or public, to “invest” in an artist, since they were already vetted by a committee of their peers. NEA grants had a symbolic value that exceeded their economic value.

The fact that NEA grants are now filtered through institutions and state agencies, to what extent that has changed things, it’s hard to tell. One thing is clear: the NEA has become more conservative in their funding patterns. Nobody is even submitting proposals to the NEA for anything controversial because the perception is, why bother? And there’s a position of precariousness that arts funding occupies on the state level and legislators sometimes use a controversial exhibition to attack all funding for the arts. They learned this in the ‘90s: create scandal around some piece of art and try to leverage that into cutting funding for the arts.

Holly Hughes in World Without End, 1989

photo by Dona Ann McAdams

C: I hear from panelists who select artists for grants through non-profit organizations in New York, that the preference is not to pick someone proposing new work because it's more of a risk. That's in line with what you are saying about the NEA not receiving anything controversial and there's this additional filtering that happens on the panels, because the organizations can’t take any risks.

S: Yes and that’s something that changed from the earlier days of the NEA, which was originally established to fund precisely innovation and experimentation in the arts and was supposed to take risks with emerging artists. It was the risk you could take as a committee of peers compared to an institution director or curator, you’re giving let’s say $10,000 dollars to a promising artist to experiment.

C: I wanted to ask about museums: In 2016 the New York Times reported that galleries are expected to partially fund museum shows for artists they represent. If this is a direction in which the art world continues to move, it will further limit the range of artists shown in museum exhibitions and the type of work created. Does this align with trends you are observing?

S: Your integrity as an institution can certainly be questioned when an exhibition is partially funded by the dealer or the artist you are showing. And that’s almost become the rule, especially with big museums shows. It’s not hidden. The dealer is in a way investing in an exhibition which is pretty much guaranteed to up the value of the artist’s work. It’s a straightforward symbiotic relationship, which appears quite productive. But then you think of what the responsibilities of a museum should be (even when private, art museums are at least tax exempt, and most of them receive public funding), about its responsibility to serve the public. . .How does that responsibility work alongside the realities of serving the interests of the art market? Is this about censorship? Not really, not in terms of actively suppressing work. Calling it censorship dilutes the very concept, which then becomes more the rule than the exception. There’s a way to talk about it, of course, when freedom becomes the exception and censorship the norm, describing all sorts of spoken and unspoken constraints on expression and even thought, but this is not the censorship we think of when we think of government removing work because of disagreements with its viewpoint. And it is useful to distinguish between the systemic condition of unequal exposure of different artistic expression and an individual act of removing something.

John Fleck, video still from Psycho Opera

Wallenboyd Theater, LA 1989, photo via YouTube

C: It effectively limits circulation of noncommercial artwork and increases visibility for saleable work, but I wasn’t thinking of it as censorship. It could reduce the motivation for artists to make experimental work when there is an expectation that you must have a gallery fund your museum show.

S: There are small and emerging artists’ spaces that are open to different types of less commodifiable work. Though, of course, it is harder to get this work in bigger or more commercial spaces. In a capitalist economy, non-commodifiable art goes against the grain and sometimes deliberately so. Ironically, though, the voraciousness of the art market absorbs even that: museums and collectors collect conceptual art and performance art which originally intended to frustrate the logic of the market. But the market is very pliable, it absorbs a lot. If anything can be turned into a commodity, it will. I wouldn’t talk about this as a free speech issue, it’s more of a structural condition that touches on speech. I find it to be more useful to talk about censorship in the narrow sense because otherwise it becomes everything and evades any opposition.

“…artists are the canary in the coal mine: when you see how artistic freedom is being constrained you become aware of the constraints put on all of us.”

C: At times it can be hard to feel that it is even a fair fight. We say we live in a society that has democratic values, but if capitalism is more powerful than the democracy, it shifts the balance.

S: Democracy is about people having the opportunity to vote and having a say in government, it’s not about economic organization. Though of course how society is organized economically determines the type of democracy you have. We can talk about Citizens United and campaign funding or voter education, about how “free” is the electoral will and how manipulated by advertising (even more so with social media micro-targeting), about how all this undermines the very premise of a democracy, of people expressing their political will. The point is that when we talk about artistic freedom, we need to be aware that this is not an issue to be tackled in isolation. The artist doesn’t exist separate from the rest of society; they’re subject to the same constraints that we all face. For artists perhaps these constraints are more tangible because there’s this romantic concept, artistic freedom, and we notice how it’s not there in various ways. In that sense, artists are the canary in the coal mine: when you see how artistic freedom is being constrained you become aware of the constraints put on all of us.